Reveling in the Roast

Pick Your Roasts Like an Expert

“I like a strong cup of coffee, one with some kick…”

“I like a dark roast.”

These are two of the most widely heard phrases by coffee roasters seeking to determine how best to please the palate of their customers. Strength, as in “I like a strong cup of coffee,” refers to how you brew your coffee, not how it’s roasted. So let’s delve into roasting first.

Coffee roasting is a near-perfectly balanced blend of art and science. Some roasters lean more towards the art, some towards the science. Many coffee creators do what they do, serve what they serve and roast what they roast. If customers don’t like it, they can go elsewhere.

Yet there are others, like Owner/Roaster of Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee Company (WFRCC), Tim Curry, who have something to meet every customer’s tastes. Sometimes it just takes a little creative exploration to get to the heart of their preferences.

Not everyone lives and breathes coffee roasting, and roasters like Tim don’t expect everyone to know exactly what the terms mean. So here we are to help…

Many Shades of Delicious

Coffee beans’ preliminary state is far from their finished: green.

These fresh little pods plucked from bushes around the globe are far from what they will turn into once placed in a roaster. That’s where their flavor- and aroma-filled nuances emerge. Their initial flavor and aroma is grassy, botanical and something most folks wouldn’t want to grind up and steep in water.

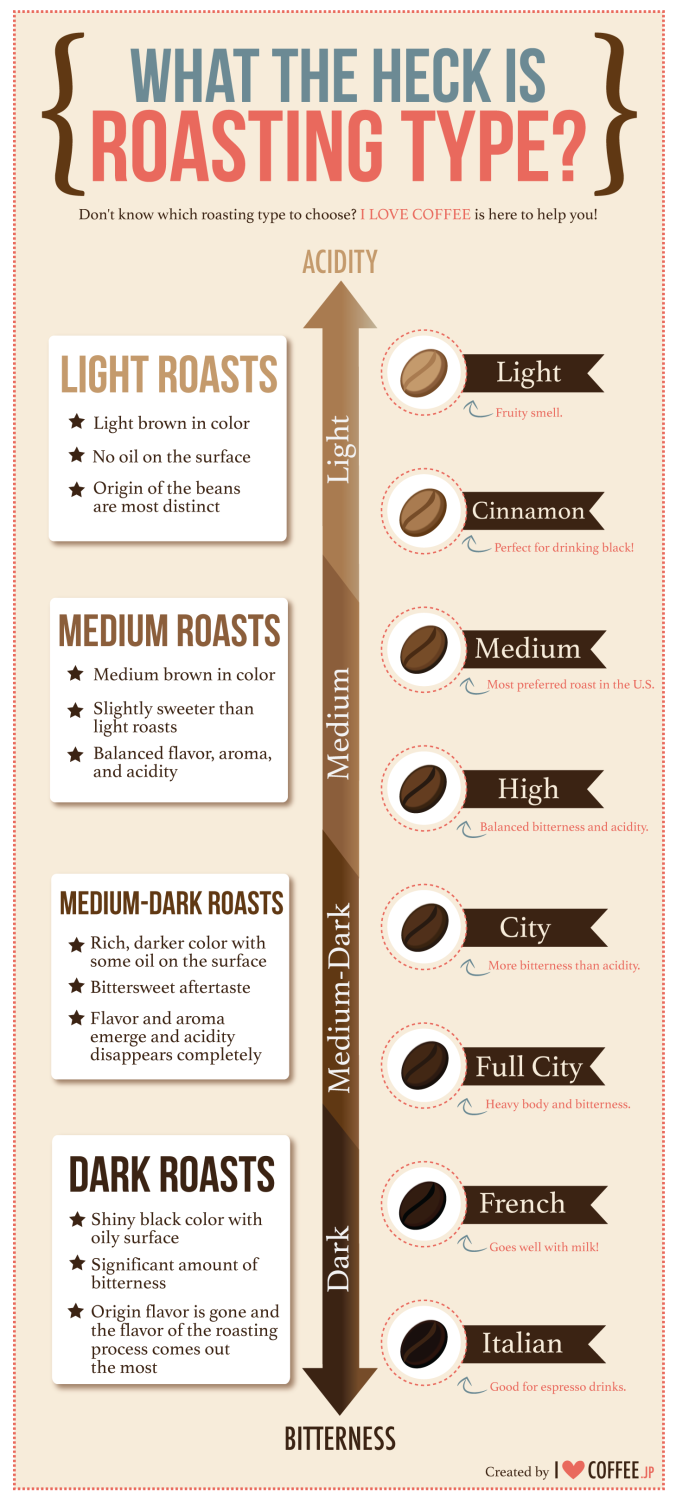

The typical strata of roasts range from light to very dark. In between are medium-light, medium, medium-dark and dark. On a numerical gourmet roasting scale, they range from 100, being an undeveloped bean, to 20, which is extremely dark. Zero is charred back to carbon. Check out this great “Guide to Roasting Types” infographic by ILoveCoffee.jp and NationalCoffeeBlog.org for some easy visual comprehension.

Tim at WFRC typically roasts his from medium-light and dark, or between 65 and 35. His happy place roasting over the open flame of his traditional Italian roaster is when he finds the ideal balance of the fruity, floral acidic characteristics found in lighter roasts, and the dark chocolatey, nutty notes of darker roasts.

This ideal balance is only found after much experimentation. That, and using the knowledge only years of roasting and studying the different regional characteristics and temperature affectations can provide.

Understand that roasters can be as diverse as the beans they curate. Minimum-impact roasters prefer lightly roasting their beans, letting the regional characteristics shine in their coffees over letting the roast drive the flavor profiles.

Others, like Tim — who is often called the “Coffee Whisperer” — prefer to experiment and let the beans dictate the roast.

“I like playing with the potentials and finding the roast style that, in my opinion, unlocks the best flavor characteristics hidden within the beans,” Tim of WFRC says.

For instance, he recently acquired some renowned Panama Geisha beans. To find the best possible roast, he began with a light roast to identify the beans’ main characteristics. Then he went to the “dark side”, deeply roasting them to see how they behaved. From the two extremes, he found a happy-roasting-medium he felt made the Geisha’s true characteristics shine to near perfection, which he then offered to customers.

A Tableau of Tastes

The next time you’re loving your coffee, hone in a bit on what it is that you love.

Do you enjoy more fruity, acidic components and flavors? More nutty, chocolatey flavors? Creamy caramel notes? A more creamy mouthfeel? Identifying your specific tastes helps determine what roast you should pick.

Here are some basic guidelines:

Light/Cinnamon Roast = more fruity, grassy notes

Medium-Light/American Roast = Acid-rich, lingering fruity and botanical notes

Medium/City Roast = Acidity begins muting, regional characters remain with creamy mouthfeel

Medium-Dark/Full City/Vienna Roast = Roast tones of chocolate and nuts move to the forefront.

Dark/Italian Roast = Slightly oily, muted acids

Very Dark/French Roast = Fully-muted acids, bittersweet chocolate notes

Extreme Dark/Volcano Roast = Burned, bitter tones

Get Your Kicks

Now, let’s go back to the caffeine question.

Contrary to popular belief, roasting generally doesn’t impact caffeine content much. Miniscule size differences aside, let’s say that most Arabica beans have an equal amount of caffeine within their little casings. During roasting each bean maintains its level of caffeine. Also during roasting the beans expand and become less dense the deeper the coffee is roasted. With this information we can have a conversation about the impact of roast on caffeine; Lighter roast coffees measured by volume will present significantly more caffeine, in the cup, than darker roast coffee measured the same way. Conversely, lighter roast coffees measured by weight will present less caffeine than darker roasted coffee, in the cup, measured also by weight. What it all comes down to is this. Brew your coffee to its best flavor, that is how I roast it, and the caffeine will be there for you as you enjoy a fabulous cup.

While we’re on the subject of “strong” coffee and “kicks,” if you’ve ever noticed that your cup of joe gives you the ability to run a marathon all of a sudden, it may be mixed with another type of bean. Robusta is an entirely different species packed with caffeine, and often mixed with Arabica by some to-remain-nameless coffee purveyors. (Never have roasted Robusta coffee, never will.)

It’s All About the Brew

Brewing the Best Cup of Coffee Possible at Home

For painters, all quality paints have the potential to create artistic masterpieces. It’s about how you use them to create the artistry. For coffee-lovers, their palette of beans can positively or negatively impact their tasting palate, depending on how they brew them. Because once the coffee is selected, it’s all about the brew.

We’ll discuss variations in coffee varietals, blends and regions in an upcoming blog. Here, we’ll talk about how to brew the coffee you currently love, for instance anything from Wood-Fire Roasted, into the best cup it can possibly be.

Flavorful Science Stuff

First, make sure you start with a bag of whole-bean Arabica coffee. When roasted, CO2 gets trapped within the millions of cells found in a coffee bean and expands them. Also found within these cells post-roast are soluble compounds that are aching to break free and flavor your cup of joe.

Only about 30% of each bean is made of soluble compounds — and only about 20% of those are tasty — while the other 70% is made from insoluble elements like cellulose and other fibers that help make up the bean’s structure.

Our mission, an entirely possible one, during the brewing process is to extract the tasty notes from the 20% and leave behind the bitter ones in the other 10%.

When dissolved by adding properly heated water to properly ground beans, fruit acids and caffeine are the easiest compounds to release and create the lighter, fruitier notes found in brewed coffee.

Lipids, which aren’t technically water-soluble but do emulsify into a cup when heated H2O is added, provide the nutty and chocolatey notes and that “oil slick” component on top; the fibers and carbohydrates are the toughest compounds to release from the beans, and add sweeter, earthier elements to a coffee cup.

Finding & Grinding

Whatever your roast and taste preference, make sure the beans you purchase were roasted within three weeks. That’s about the shelf-life of roasted beans before they start losing their volatile flavor profiles. Volatile flavor profiles are a bit moody, but they’re also those that we love in our cup, like spicy, floral and fruity notes. The static flavor profiles that are more resilient are the bitter 10% we made mention of above. No one wants those hanging around once the good ones start disappearing.

Pre-ground beans take far less time. Roasters who truly care how their coffee tastes when brewed will have a “Roasted On” date clearly listed on their bags.

Then, let your brewing method — discussed in the next section — dictate your grind. Best for control is a hand-crank grinder, but Burr grinders work well also. Blade grinders unfortunately create too many flavor-affecting inconsistencies and the friction created can scorch beans.

Grind is so important because the more water that comes into contact with a coffee bean’s cells, the more it extracts from them. Solubles carrying the less enticing flavor characteristics are thankfully the toughest to extract, so controlling the time water comes in contact with the bean cells makes it easier to control the resulting taste.

This can be done by breaking the bean down into smaller parts by grinding into fine, medium or coarsely ground coffee. The finer the grind, the less time it takes for water to extract the same solubles from the cells of the beans.

This great article on HandGround.com entitled An Intuitive Guide to Coffee Solubles, Extraction and TDS explains:

“Grind size doesn’t determine what is being extracted, it determines how long it will take for the water to reach all of the cells. Hopefully it is starting to become clear how time and grind size are inversely linked. When we increase one, we must decrease the other.”

For instance, using a consistent water temperature, the same number of compounds can be extracted from a fine grind in 30 seconds as can be extracted from a medium grind in 120 seconds, or a coarse grind in 240 seconds.

HandGround.com’s article elaborates:

“The solubles released during extraction determine the flavor and Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) determines the intensity of those flavors. This is similar to music if you think of solubles as the music itself and TDS is how loud the volume is set. Increasing TDS will produce a stronger flavor but turning it up too high may cause some flavors to overpower others completely.”

Now is when the method comes into play.

Just Add Water

Before we get to brewing, a note on the importance of water temperature…it’s super important.

Only ten degrees separate mediocre from perfection. Whatever your brewing method of choice, the water needs to be between 195° and 205° Fahrenheit. Anything below may not extract the best flavor compounds, anything higher may scorch them, leaving you with a burned taste in your cup.

Usually this temperature can be acquired just before your water gets to a rolling boil. At high elevations, water conveniently boils at around the correct temperature for brewing coffee, like here in Reno, around 203.8°. But use a thermometer to be absolutely sure.

If using a device requiring a paper filter, it’s best to rinse the filter first with a bit of Brew temperature water before using to eliminate any impurities within it that may affect coffee taste. Let the rinse water drip through into a cup and discard.

Then, soak your grounds first in situ, meaning wherever they rest before brewing, such as in a French press or paper filter, add a bit of water to them to help them “bloom”. This pre-infusion process helps to release any residual CO2 left in the beans after roasting that can block water from getting to the flavor-filled solubles.

Agitate the grounds to ensure all the CO2 is released; once the bubbling action you’ll see stops, you’re good to brew.

Optimal extraction level from within the beans is about 20%, meaning 20% of the mass of the coffee beans ends up in our cup after being dissolved by water. If your coffee is bitter, solubles may be over-extracted and you may need to make the grind coarser and lessen the brew time. If it’s sour and lacking in sweetness, you may be under-extracting the solubles and need to increase the brew time using a finer grind.

Contraption Savvy

There are nearly infinite amounts of contraptions available to brew coffee these days. From the Keurig to the Chemex, even a new device called the Aeropress, your options are endless — unless you seek brewing perfection.

Around WFRC, you won’t find a drip coffeemaker, (unless we’re using it for comparison’s sake.) Drip coffeemakers take so long to pump out a single pot of coffee, letting the beans lounge in whatever-temperature water, that it extracts every last flavor profile from the bean, including the ones we don’t want.

Instead, around the roastery you will find a French Press, an espresso machine, and pour-over systems including a Chemex(tm).

No matter the system, the ratio of ground coffee to water must be delicately balanced. Owner of Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee Tim Curry feels the ideal ratio is 15:1, meaning one part coffee to 15 parts water. Two tablespoons of ground coffee to six ounces of water is just about 15:1.

Increasing the ratio of coffee to water will make the brew bolder, decreasing will lighten the flavors significantly. Too much adjustment will either leave the wonderful flavor components behind if too much coffee is used, or extract too much of the less desirable components, leaving the coffee both weak and bitter.

Pour-over systems like the Chemex, or one of the BPA-free plastic models, use a paper filter to help prevent bitterness by capturing the lipids that cause it. Only 1/10th of lipids in a bean can get through the paper filters, so the resulting taste and mouthfeel tends to be crisper.

A French Press eliminates the need for a paper filter, exchanging it for a built-in metal mesh filter. This allows lipids to pass through into your cup creating a creamier and more viscous mouthfeel.

French press users simply add the desired ratio of grounds to the device, then let them bloom before filling the press with the appropriate ratio of water. Allow to sit for four minutes before pressing the plunger and pouring brewed liquid perfection.

In your pursuit of coffee perfection, pack up that ol’ standby countertop coffee maker and pick either a French press or a pour-over system. Then follow these steps to make each day a bit more flavorful.

Steps for the Perfect Brew:

1) Pick your brewing system.

2) Heat the water to 195°-205°.

3) Grind the beans appropriately.

4) Measure the grounds to create the 1:15 ratio of grounds to water.

5) Bloom the grounds for approximately 30 seconds.

6) Continue pouring perfectly heated water over the beans, six ounces of water to two tablespoons of grounds is

ideal. With a scale this would be 20 grams of ground coffee and 300 grams (12 ounces) of water.

7) Let the fantastic flavors drip into your cup for approximately three-four minutes. Plunge if using a French

press. Discard filter and remove contraption if pour-over.

8) Enjoy!

9) For fun, take a selfie of yourself enjoying your first sips and tag @woodfireroasted on Twitter, Facebook or

Instagram.

Crafting a Masterpiece in a Cup

Just that first taste of the world’s favorite dark, steaming, aromatic elixir equals rejuvenation for many. While a multitude of humans partake in a coffee ritual daily, many don’t know much about the series of craft endeavors that lead to what’s contained in their cup.

More details on the process from crop to cup will be shared in proceeding blogs, but today we’re speaking on the crafting of a coffee masterpiece with Owner-Roaster Tim Curry of Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee Co. (WFRC).

First Steps in Coffee Crafting

Merriam-Webster defines the word “Craft” as:

1) Skill in planning, making, or executing: Dexterity

2) An occupation or trade requiring manual dexterity or artistic skill

Coffee is crafted through multiple, mutually exclusive steps that eventually intertwine to produce the plethora of types on the market. Each affects the finished product in its own way. Here’s an outline of those steps.

Beginning with farmers planting coffee trees, the many crafts involved in getting to that cup of Joe includes harvesting, processing, milling, roasting, grinding and brewing. One common denominator exists, though: a person manipulates a thing in their pursuit to find glory in the cup.

“Sleep is Overrated”

A phrase muttered many times over by WFRC’s Tim Curry, learned while first experimenting with coffee roasting. For roasters and other artisans the world over, sleep is overrated while pursuing perfection of their passion and craft.

Tim’s coffee roasting pursuit began over his kitchen stove, formed from a love of coffee and a curiosity about how he could create it himself. After finding and ordering green Ethiopian beans, he set about experimenting with roasting them in a pot he still keeps in the roastery today. It serves to remind him of his humble beginnings.

That first batch of beans he roasted proved inspirational. Not only did he revel in the flavors he coaxed from the beans, he exclaimed, “Wow, that’s what coffee is supposed to taste like!”

Seventeen years of experimentation and learning how coffee behaves later, Tim’s expertise has increased while the humbleness remains. Turns out, learning the craft of coffee roasting is an ongoing process that may never be truly perfected, as others’ palates are an ever-present and variable factor…one of myriad variables and factors, actually.

His novice status was the perfect starting point, however. “I learned more about roasting by not knowing what I was doing,” Tim shares.

Coffee’s Canvas

Coffee roasting is an experimental artistry—the beans are the paint brush, while the roasting technique is the paint. Once the bean-producing regions and bean’s typical traits are learned, for example Ethiopian beans are renowned for their earthy characteristics, there are many different roasting methods used to encourage particular flavor profiles out of them.

While all are ultimately controlled by a human, some rely more on a machine’s consistency than a person’s level of artistry.

It’s like buying an original work of art instead of a lithograph. An artist’s hand-painted works will always be entirely unique—brushstrokes may vary slightly, and some colors may be a shade different from one version to the next, if reproduced, but the overall skill level is foundational.

When lithographs of an artwork are created, identical replicas can be easily produced by pushing buttons on a machine, artistry isn’t as big a factor.

Some roast beans using easily regulated and temperature-controlled gas roasters, which does little to influence the coffee’s flavor profiles…this is seen as a benefit by roasters who focus more on bringing out the beans’ regional flavor characteristics.

A bit of the art and potential unique qualities can be lost during this process, however. Think about cooking a steak on a gas grill versus a wood-fired one. Some aficionados find added depth and flavor in the wood-fired fare versus the gas-cooked. The same applies to coffee. Wood-roasting coffee increases the variables as well as the flavor profiles.

Old-World Craft

Manipulating a natural element like fire to produce a delicacy like coffee is an art; fire adds a temperamental biological factor to the roast, while consistency can usually be found where the beans are sourced.

Roasting is singularly the most impactful step in creating an outstanding coffee. Tim Curry has been called the “Coffee Whisperer” by food writers for his knack of listening closely for the cracking beans to tell him precisely when they’re ready.

He notes that underdeveloped, green coffee is steely tasting. But there’s no room for metal in a coffee’s flavor when a bounty of other enjoyable ones can be coaxed from the beans. And smoke is not one of them, even when talking about roasting over a fire.

Here is where chemistry meets art in this particular craft. The longer you roast, the more the process drives the flavor profiles. Based on the type of roast desired for particular beans, knowing when to start cooling the beans is part of the science. For a wood-roaster, many factors come into play that can influence the final coffee flavor, from the choice of wood and beans, to the length of the roast and even the possibility of aging beans in whiskey or wine barrels. This is the art.

Well-rounded, balanced coffee is the goal. The whole mouth welcomes the flavor and depth of a well-rounded coffee, versus the sharp, almost-pointy sourness that can stab a palate. When all characters—like the beloved fruity, floral, chocolate and earthy notes—are equal in their presentation, an idyllic coffee has been crafted.

And the crafter sets about creating his next masterpiece.

Finding the Right Coffee for You:

There is a lot that goes into your morning cup. 70 years ago you just went down to the corner grocery and picked up a can of whatever pre-ground that you preferred. The coffee was then brewed with some magical formula, a measurement, most likely determined by the matriarch of the kitchen, thrown into a percolator basket then put on the stove to do its business. Soon you would have a hot cup in your hands. Growing up in the 60’s and 70’s this is how I was introduced to coffee. It wasn’t until I embarked on my restaurant career that I was introduced to the auto-drip coffee brewer.

With today’s plethora of brewing systems, all designed to provide the “best” cup of coffee, grinders, and coffees to choose from how do you decide what is best?

Ultimately, the coffee you enjoy is the coffee you should drink. Make it the way you like it and enjoy it.

Let’s take a few minutes to determine how to decide what is best for you.

I think a great starting point is to get you brewing needs in order. Select your brew system; you may have already done that, so be certain to know that system and its function well. Know how your grinder works and the best way to ensure consistency in the grind. Know the best way to properly dose the coffee as well as the best way to store your coffee.

Then:

1) Make sure you are using fresh coffee. If the coffee is old and stale you cannot get the optimum flavor that you are looking for. Coffee, once roasted, has an effective shelf life of about 3 weeks. The staling effects of oxygen will cause whole bean coffee to lose as much as 80-90% of its volatile flavor profile in that time. Ground coffee will be impacted in the same fashion in just a few days.

2) Be sure to grind properly, a good general guide to grinding is:

a. Turkish, equal in size to powdered sugar. Very Fine

b. Espresso, should be ground for your specific espresso machine. Follow the instructions.

c. Pour over / cone filter, the same size as table salt

d. Flat bottom filter, same size as kosher salt

e. French Press, medium course; a bit more course than for the flat bottom filter

f. All others should be coarsely ground and of consistent size.

3) Dosing your coffee. In the shop we use a standard formula, 15/1 ratio of water to ground coffee. Or, you can start with an approximate measure of 2 TBSP ground coffee for every 6 ounces of water. (That is approximately 15/1) Then adjust to your personal taste. Remember, coffee is all about your enjoyment.

I told you there was a lot that goes into your morning cup, but once you have a system in place it is easy to duplicate on a daily basis.

4) Water temperature is CRITICAL to your coffee brewing. There is a 10 degree window for water temperature for proper brewing. That window is 195°F-205°F. If the water is too cool the flavor oils will not properly dissolve leaving flavor in the grounds. Too hot, and the oils can scorch leaving a burnt flavor in the cup.

Most home brewers won’t do an adequate job on water temperature so be certain that the one you are buying does reach the proper brewing temp.

Now that you have everything in place and understand its function you can start trying different coffees with confidence. You can stop in the shop and discuss your coffee preferences (really you can do that right away so we can work together through the whole process if you like.) But in deciding on your coffee there are a couple of questions to ponder.

1) What is the general depth of roast you prefer? We have a broad selection of coffees and varying roast degrees to meet with every palate.

2) Do you like bright and lively coffees? Creamy, round and smooth? Or, dark and bold?

3) Are you willing to experiment?

4) Do you prefer single origin coffees or blends?

5) What are your preferences on acidity and caffeine?

One of my favorite things is to talk coffee! It is my desire to help you get the same enjoyment out of your cup as I get out of mine. Please, if you have the time come to one of our tasting events or schedule one of your own. We can dedicate some time to taste and discuss all things coffee.

And, remember, coffee should be both fun and flavorful.

Roasting history: Wood-fire, the West, and Reno

There’s a special mix of old and new in Reno. It’s one of my favorite things about this place. When I started roasting coffee, they were still driving cattle through town for the rodeo. If you look at the explosion of growth in the Midtown area, you’ll see a huge number of old buildings brought beautifully into the 21st century. We’re seeing tech giants like Tesla and Apple coming to our fair city to complement the gaming we were built on. This blend of old and new is reflected in all aspects of Reno’s culture, and roasting coffee over a wood fire perfectly exemplifies it.

Until the mid nineteenth century, most coffee was sold green and needed to be roasted by consumers before they could brew it. The green beans are better for shipping and storing because they keep longer and take up less space than roasted beans. With significantly slower and more costly shipping than we enjoy now, not to mention inferior storage methods, spoilage and maximizing capacity were both big concerns. There was also the concern of early commercial roasters cutting their roasted and pre-ground coffee with cereal substitutes, which helped keep hearth roasting coffee over wood fires the standard into the twentieth century, particularly outside of major cities.

Since the sixteenth century, in Italy it was common to see your neighbors out roasting coffee on their patios. The tradition crossed borders, the oceans, and time. Even today many people roast their own coffee at home still; although roasting over a wood fire is rare. Below are some examples of home hearth roasters I have hanging around the roastery.

This old-world appeal is part of why I enjoy wood-fire roasting today and why I thought it would be a natural fit in the Biggest Little City. Of course, I use a wood-fire roaster that handles quite a bit more coffee, about 35 pounds per batch to be precise.  The roaster does a much better job of heating the beans evenly than the old, hand-cranked models above, utilizing convection and conduction for a better roast, but it still maintains that old-world flair I love.

The roaster does a much better job of heating the beans evenly than the old, hand-cranked models above, utilizing convection and conduction for a better roast, but it still maintains that old-world flair I love.

To me, the difference between gas-powered roasters and wood-fire roasters is a bit like the difference between digital and analog. There’s an artistry and nuance in the latter that the former does not allow. I like the temperature dynamic of wood-fire roasting. The beans get directly exposed to the smoke, too, which softens the flavor. This effect is more pronounced in darker roasts and assists in coaxing flavors out of the bean.

A smaller roaster allows me to tend to each batch individually, making adjustments for each kind of bean and what state it’s starting in. Using a wood fire that demands my attention during the roasting process also keeps me in close touch with beans as they roast. This is where the art of it comes in. By design, this isn’t a mass-produced, conveyor-belt kind of operation.

A smaller roaster allows me to tend to each batch individually, making adjustments for each kind of bean and what state it’s starting in. Using a wood fire that demands my attention during the roasting process also keeps me in close touch with beans as they roast. This is where the art of it comes in. By design, this isn’t a mass-produced, conveyor-belt kind of operation.

Roasting over a wood fire may make me a black sheep in the world of coffee, but that fits my style just fine, and I think it fits Reno’s style even better.

Underdeveloped coffee: It’s not tasty being green

Imagine a combination safe that opens to reveal a different treasure for each combination. Some combinations unlock marvels; others leave you staring at an empty metal box—and there are a myriad different treasures in between. This is the metaphor I like to use for roasting coffee. The fresh, green bean is the magical lockbox, and the skill of the roaster is the combination.

Too often, roasting is reduced to the exterior color of the bean, which, in the case of our locked safe, is a lot like trying to judge the treasure inside by what color it’s painted. The interior of a coffee bean holds flavor complexities that need to be coaxed out. When coffee is roasted to the color of the outside of the bean rather than allowing the interior to reach a similar roast profile, many undesirable taste characteristics come out. These can include corn, grass, stem, wheat, and any other savory bitterness you can imagine might come from biting directly into the plant itself. This greenness is referred to underdevelopment, and it’s become a trend known euphemistically as “minimal impact roasting” that affects the solubility of the coffee—and, of course, the taste.

Roasting simply to minimize roast impact does one thing very well: it allows the roaster to exemplify the regional character of the coffee. By holding firm to this approach, the roaster avoids many opportunities of full, round, and flavorful coffees. I have left many coffee houses that serve these minimal-roast-impact coffees only to have a decidedly unpleasant, long aftertaste disturb my ride to my next destination.

I strive to avoid these green flavors coming through in the cup in favor of rich, sweet chocolate, caramel, and nut flavors. These work to enhance a fruit-dominant character, while lengthening the finish to a full, round, and pleasantly lingering flavor bomb. These roast-driven characteristics are the boon of a well-developed coffee.

Seeing green

Underdeveloped coffee beans can be tricky to spot. While one might intuit that a quick glance would reveal an under-roasted bean, you simply can’t see how well developed a bean is from the outside. Very basically, it’s only the end temperature of a roast that determines its color. Think of it like searing an ahi steak, but instead of locking the good flavors in, you’re sealing in unpleasantness that will lie in wait until it is ground and brewed. You’re also completely locking in many aromatics and even some of the caffeine because of the insolubility of an underdeveloped roast.

So how do you tell if a bean is underdeveloped? Are you grinding one coffee more finely than another of similar color? Struggling to slow down espresso shots? You’re most likely dealing with an underdeveloped coffee. Can’t easily crack open a bean with your fingers? Likely underdeveloped. Can you see a color difference between the exterior and interior of the bean after you do finally crack it open? Most definitely underdeveloped.

Wood-fire roasted to perfection

Roasting to a darker color doesn’t necessarily make the coffee developed, and a light roast doesn’t automatically preclude it from being so. While roasting darker can certainly help with an underdeveloped roast, it often leads to an overdeveloped exterior. Sure, this means that what’s left is nice and soluble, but everything tasty has been cooked off and lost to the roasting process.

My techniques allow the center of the bean to catch up to the exterior a couple of times during the roast, not late in the process when this window has closed. The precise methodology I use has evolved over the years as I’ve grown as a roaster. As the beans roast, sight, smell, and sound help me get a good idea where the beans are in the roasting process. Color only begins to play a larger role as the center of the beans catch up.

I began to recognize the real impact of temperature as my skills developed. Finding points at which it’s best to apply more heat and learning when to ease off are nuanced techniques to say the least, particularly when trying to predict how these early changes will ultimately manifest in the cup. Through modifying my roasts minimally, I’ve developed techniques for maximizing the development of the whole bean, not just the exterior color.

Roast characters are often a great addition to the flavor of a coffee. Imagine having a very fruit-driven coffee with bright, lively acidity. With small modifications to the roast development it is possible to, with a small impact to these desirable traits, add a hint of chocolate tone and reduce the overall acidity for a creamier mouthfeel. By doing this you totally change the depth and feel of the coffee in your cup. This is how I roast.

I understand the desire to allow what’s essentially the terroir of the coffee bean come through in the cup. In the end, the best cup of coffee is the one that you like to drink (supplanted sometimes by the one in closest proximity on a Monday morning). Minimal impact roasting certainly has its place, but I have found that with some coffees the true wonders come through at just slightly more roast impact.

The evolution of a roaster: 14 years of obsession

On July 1, 2001, I opened Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee. The first decade flew by quickly enough; it’s hard to believe we’re an additional four years past that. When I started out roasting coffee beans, it was just over my kitchen stove. I’ve obviously learned quite a bit since then and refined my technique considerably, but it was there in my kitchen in the early days that I discovered I could craft a coffee that I really liked—and I already knew that I liked great coffee.

In the beginning… there was a lot of smoke

My first “roaster” was a three-quart sauce pan held over an electric range. I spent hours and hours adjusting that process and really getting to know the beans. I learned a lot about the way coffee behaves during the roasting process. I also learned the importance of meeting certain “marks” in while batch roasting. This was when I began to recognize how to use all of my senses to gauge how the coffee was coming along. If you listen just right, you can hear the beans relay precisely when they’re ready.

It wasn’t too long before I was hooked on roasting. The electric range worked, just not particularly well, and the six or eight ounces I could roast didn’t go very far. I needed something bigger and less hokey, so I set to the task of having my own roaster built. It was a simple, charcoal-heated drum. I could roast about two full pounds at a time, which was certainly an improvement, but this low-tech unit definitely came with some drawbacks.

My home-built roaster had a hand crank on the side, and the process involved an awful lot of smoke in the face, if you were doing it right. Getting the thing to breathe properly was a creative journey unto itself. It was with this roaster, though, that I began to acquire my first commercial accounts, small as they were, and realize that I might have a future in producing fresh, whole bean coffee. I roasted for nearly a year and half on this roaster, learning more every smoke-in-the-face-filled day about the need to employ rigid consistency measures between batches.

I toiled day after day with my hand-cranked roaster and earned enough to start getting serious. I started shopping around and ended up purchasing the roaster I use to this day: a 15-kilo Balestra wood-fired drum roaster. I set up my first real shop during this time, too.

This is when the fun really began. Sure, I got to leave some of the face-smoke behind, but now I had to learn a new method of roasting and strive to overcome the inherent obstacles that come along with wood roasting. All the while, I was teaching myself how to build a real business, which comes with its own challenges. I should note that both have become incredibly rewarding experiences. I would, however, recommend doing them separately if at all possible.

Stoking the fires

As I honed my craft and came into my own as one of less than a dozen wood roasters in the country, my knowledge and standards grew. Today we source only Specialty Grade, 100 percent Arabica coffees. We roast to order as much as possible to minimize waste and, more importantly, maximize freshness. It’s rare that we have more than ten or fifteen pounds of coffee roasted and languishing on a shelf—and we only keep that amount around in the event that someone stops in unexpectedly to buy a few pounds.

When beans are roasted over a wood fire, the sharp edges of the coffee are softened. Acidity is muted on the palate. The beans retain their regional character, and, in fact, it sings in them. Complex flavors arise, flavors I’ve learned to draw out or temper in the roasting process, depending on how I’d like a given roast to turn out.

Generally being a traditionalist, I felt that employing an age-old and time-tested method for roasting was in order for my business. I struck by the process, wooed. I wanted to come as close as I could to imitating the old world style that was employed for centuries, roasting coffee over the cooking hearth. It’s a very hands-on, artistic way to craft roasted beans, much more so than computer-generated roasting profiles and degrees. Both methods have their place, but it was clear early on which way I wanted to take my craft and my business.

One of the more fun aspects of coffee roasting is the constant growth. I so enjoy keeping up with trends not only in roasting style but in boutique coffees. In 2011, we here at Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee had a phenomenal experience that can only be attributed to this constant learning. Ken Davids and Justin Johnson of CoffeeReview.com gave our Kenya Nyeri Gichatha-ini AB Signature Series a 97 out of 100 in a blind tasting. It’s the highest rating they’d ever given, and we had the honor of having the ninth coffee to achieve it in their fifteen years of reviewing.

Our life blood is regular and devoted customers, of course. There is something special, though, about one’s craft being recognized on such a large scale. Our Signature Series roasts are sourced from carefully selected small lots grown with care. It’s finding the true gems from amidst a world of coffee growers and coaxing the subtle characters and nuanced flavors out of the non-descript green coffee seed that is my passion, and bringing that to friends, my joy.

Roasting in the moment

We’re fortunate to have a community of followers and dedicated clients who appreciate our work. Today, Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee is appreciated in more ways than I could have anticipated. We’ve been a part of award-winning barbecued ribs. We’re a part of FiftyFifty Brewing Company’s Eclipse Barrel-Aged Imperial Stout, a beer that’s so popular they actually sell futures.

However people choose to enjoy my efforts, I like to stress the importance of being with the experience in the moment. In other posts, I’ve talked about developing a coffee ritual to get the most out of every cup. I take pains to make sure my roasts stay flavorful through the final sip of every cup, and when you take time to enjoy that, it can be a truly wonderful experience. Take the time to find your perfect cup of coffee—the perfect grind, the exact proportions, the precise brew method, it all works together to help you get everything out of our roasts.

Our success has been such that we’ve been able to give back to the community that supports us. Since 2010, we’ve donated over $10,000 to local nonprofits. We’ve also helped numerous children’s fundraising efforts over the years, offering our coffee to them at a big, so they can resell it to raise money.

Self-Evaluation is ongoing, particularly around this July 1st anniversary date. I think about our business dealings, product decisions, personal interactions, and client development, and I try to figure out exactly what Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee is all about. After much dwelling and deliberation, the answer I always come back to is this: we are about the coffee. Fourteen years later, I stand by it. I live it. And I drink copious amounts of it.

From roots to roast, crop to cup: A brief look at coffee’s infinite variability

From roots to roast, crop to cup: A brief look at coffee’s infinite variability

It might not be something you want to think about while brewing your pick-me-up at sunrise, but coffee is staggeringly complex. It’s more convoluted than simply asking for Mokka-Java or Colombian and being done with it. The factors that influence and nuance that morning cup are nearly infinite, and they interact with one another. Change one thing, and you change them all.

As a roaster, I’m always intrigued to find out what people call their favorite coffee. I try to match those preferences with my coffees, but it can be quite a challenge. I have to work off of my perceptions of those stated flavor preferences, which isn’t the most straightforward process. It would be great if everyone’s taste buds, olfactory nerves, and brains worked together in the same way, but that’s clearly not the case. I roast coffees to get what I interpret to be the best flavor from the beans. To a degree, every roaster does this, but some aim just for a flavor profile they think will sell, others try to exemplify the character of the bean, and still others simply go through the motions of what they believe to be the “correct” process and apply it across the board.

From the very ground in which the seedling is planted to how you end up grinding the beans and brewing them—even how you sip, slurp, or gulp it down—everything affects the taste of coffee, some things more than others. Here are ten of the biggest variables influencing your cup of joe:

1. Origin. Coffee is grown in the equatorial band around the globe between the Tropic of Cancer to the north and the Tropic of Capricorn to the south, known generally as the tropics. Dozens of countries produce coffee inside this strip of the globe, and each one has different circumstances that affect the green coffee seed from the very start.

2. Subspecie. There are dozens of subspecies of coffee, known as varietals. Every varietal has its own story. Some come from selective breeding and adaptation to new regions after being transferred by horticulturalists. Some were created with various grafting techniques. Some were cooked up in laboratories in attempts to minimize susceptibility to disease, infestation and drought. Many trace their lineage through several or all of these, and every single one has a slightly different flavor profile.

3. Soil. Differing soil conditions also play a role in fruit development. Just like terroir has an effect on wine, it also affects coffee. High iron content in the soil can add a metallic taste. Phosphorus can increase acidity in the cup. While they haven’t all been isolated, you can be sure that for every compound found in the earth in which the coffee is grown, there’s a difference in the taste.

4. Microclimate. Differing microclimates contribute a surprising amount to the final cup. Sometimes a certain section of a hillside will get different breezes, moisture, sunlight, or rainfall, each of which in turn affects the plant and therefore the fruit.

5. Macroclimate. Of course, if a small change can alter the taste, a large one undoubtedly does, too. Coffee grown in a sheltered area away from prevailing weather patterns will have a substantially different outcome than coffees grown elsewhere in a given region, and coffee grown in an entirely different part of the world more prone to fog or sea breeze, high heat or wind, humidity or harsh weather will do the same.

6. Altitude. The higher one climbs, the thinner the air. I know it. You know it. And coffee definitely knows it, too—as do the various pests that attack it. Coffea Arabica, for example, is very susceptible to disease and infestation and therefore requires higher elevations to thrive. There are other advantages to this as well. Higher elevations place more stress on the plant causing it to put more effort into reproduction (the seed), in turn giving Coffea Arabica deeper and more complex flavor profiles than its Coffea Robusta counterpart.

7. Processing. Yes, even the act of removing the fruit from the seed can change the taste of a coffee. In fact, it can be the single largest contributor to a bean’s flavor profile. The difference between an identically grown varietal processed two different ways (e.g., being washed and dry-processed versus being wet-processed) can actually be greater than the difference between two coffees processed the same way from opposite sides of the globe. It’s that big of a deal.

8. Roasting. The coffee seed is transformed into a palatable product and made ready to brew through roasting, and it can make or break a bean. There are somewhere in the neighborhood of 1,400 roasters in the U.S. alone. Roasters range from mass-producing, industrial corporations to micro-roasters like us at Wood-Fire Roasted Coffee. As a micro-roaster, I have the opportunity to spend time with bean, to get to know it and really bring out the best in it. I roast to achieve total cup balance. This can mean maximizing characteristics like acidity and terroir, or downplaying them in a roast. The goal is a cup that sings from start to finish and stays true to its ideal flavor.

9. Grind and portion. This is where you (or your barista) come in. These are very important steps in the pursuit of a perfect final cup. Believe me, you can have the best coffee roasted to draw out everything wonderful about the bean, and if you don’t grind the coffee right or use the proper amount, you will always come up shy of greatness. My standard is 1 gram of coffee to 15 grams of water. Start there, and adjust to your taste.

10. Brewing. The penultimate step, right before you bring that cup to your lips, is brewing. You’ve selected your coffee. It’s fresh. It’s from your preferred roaster, and you have put in the effort to ensure that the portion and grind are just right for your brew system. I always recommend the French Press for brewing, as it gives the most control over all aspects of the brewing process. A couple of great alternatives: The Chemex brew system or the Clever Dripper. I never under any circumstance recommend an auto drip coffee maker or percolator. Please ask why next time you are in the shop.

Neither of us, nor the growers, have control over every aspect we’ve covered, which is why trust and experimentation are sort of meta-factors in flavor. You need to trust that your roaster can pick the right crop and roast it to the height of its potential consistently. Once you’ve got it, experimenting to really zero in on what you like best is key to finding your cupful of Nirvana. The next time you wrap your hands around a piping hot mug of coffee, spend a moment thinking about all of these factors and the myriad others that had to line up to get you—and the coffee—to that perfect place.

Warming up to Cold Brew

The brewing of coffee, that nectar of the gods, is steeped in tradition. The best and brightest of many a culture have been powered by this elixir, and many of them have devoted serious time to getting the perfect cup out of every brew. Of course, in the case of coffee, perfection is a relative term, or at least a subjective one. Even dip your toe into the vast pool of information available online about coffee brewing methods and you’ll find evangelists espousing their preferred method of brewing and spouting vitriol about others.

The big secret is that the best method for brewing coffee is the one that you like best. There are benefits to be considered for each method, and they range from ease to economy, health to heat, caffeine to convenience, and everything in between. As invariably as Earth’s axis tips our hemisphere towards the sun this time of year, warm weather always starts the conversation about cold coffee. Numerous options exist for making your daily cup cooler as temperatures climb, but one method that’s been steadily growing in popularity is cold brewing—and some take it hot. Its roots run deep, with devotees in the American South tracing their love for the stuff back generations. It’s not for everyone, but it might just be for you.

The Skinny on Cold Brew Coffee

In contrast to the relative speed with which a hot cup of coffee can be brewed, cold brewing coffee takes a time commitment of around twenty hours. As opposed to the aromatic, acidic coffee with a bite that hot brewing produces, cold brewing rewards your patience with smooth, sweet coffee concentrate. To understand why, it helps to understand some of the chemistry behind it.

Coffee beans are chock full of oils, acids, and aromatic compounds that are collectively referred to as coffee solubles. Every method of brewing involves releasing these coffee solubles into water, and variations in time, temperature, grind, and water-to-grounds ratio all contribute to different flavors coming out of the process. Each of these compounds has different degrees of solubility and volatility, which are basically the ability for the compound to dissolve into the water or be evaporated into the air, respectively.

Generally speaking, the ideal temperature range for extracting most coffee solubles is between 195 and 205 degrees Fahrenheit, which is why hot brewed coffee is often referred to as being more full-bodied than its colder counterpart. Solubility and volatility both increase with temperature, and it’s the latter that is responsible for the incredible aroma of a fresh brew. Also increased at higher temperatures are oxidization and degradation. Oxidized oils taste sour, and acids taste increasingly bitter as they degrade.

The decreased extraction rate of cold brewing is why the amount of grounds used is about double compared to a hot brew and the time it takes is hours longer. Oxidization and degradation are also slowed way down with the cold brewing process, and some compounds attributed with unfavorable tastes and many acids only dissolve at higher temperatures. As a result, cold brewed coffee is almost completely lacking in sourness and bitterness. With cold brew, chocolates, fruits, flowers, and nuts come through in the flavor profile, and there’s a certain sweetness in spite of the beans’ residual sugars not being fully extracted. Cold brew also only has about one-third of the acid, which makes it a lot easier on the teeth and stomachs of drinkers.

At this point, the question on everyone’s mind is, of course, “but what about the drugs?” Caffeine is extracted early in the brewing process, and brew time does not determine its concentration. By using twice the grounds, you’re effectively doubling the caffeine in the concentrate you make by cold brewing, but again, it’s meant to be a concentrate. You’re meant to be cutting it with water, milk, or whatever’s your pleasure, not drinking it straight. At the diluted level, you’re still getting your regular fix.

You Can Do It: How to Cold Brew It

For what seems to be a fairly straightforward and simple brew process, there are a staggering number of even more staggeringly expensive machines out there for making cold brew coffee. Of the devices specifically designed for the job, my favorite is the Toddy, which was developed by a chemist largely responsible for the popularity of cold brew outside of the South, where the traditional apparatus is a simple lidded Mason jar.

After many years of cold brewing, I’ve refined my own technique to suit my taste, but it’ll be good place for you to start and several of these techniques can be translated to other cold brewers, like the aforementioned Mason jar.

1. In a 38-ounce French press, add six ounces of cold, preferably filtered, water to the empty reservoir.

2. On top of this, weigh out 7.5 ounces of coarsely ground coffee (a little more coarse than a standard French Press Grind) and add that to your six ounces of cold water.

3. Add another 16 ounces of cold water, pouring it slowly over the grounds to moisten all of the coffee.

4. Wait five minutes for the coffee to bloom and soak up the water.

5. Add the final eight ounces of cold water slowly and steadily, taking care not agitate the grounds too much.

6. Cover loosely with a plastic bag, and let your concoction sit for 20 to 24 hours.

7. Just plunging the French press won’t get out all of the grounds, so have a secondary filter ready.

This produces the concentrated coffee mentioned above. You’ll want to mix this between 1:1 and 2:1 with water or milk to your personal taste (note: cold brew is known for going wonderfully with dairy—try pouring your concentrate over chocolate or vanilla ice cream; it’s fantastic). For hot coffee, mix concentrate with boiling water (don’t boil the concentrate itself!). Take some time to vary all of the elements at play here. Brew time, grind, even grounds-to-water ratio—all can be tweaked to net a cup of cold brew that is perfectly suited to your tastes.

Mindful Tasting: Get More from Every Cup

In this grab-and-go world, stopping to smell the roses, or should I say taste the coffee, quite often gets passed up. As you may have read in the last blog post, I recommend having a coffee ritual centered around the quality, brewing, and flavor of coffee. I also recommend setting aside 45 minutes to an hour at least once per week for this ritual. Why? The idea is to develop awareness of your morning cup and make enjoyment more accessible when things are hectic.

Happiness studies show that mindfulness, being in the moment, increases enjoyment—no matter what we’re being mindful of—and that when our minds wander, even while we’re doing something we love, it diminishes the experience. When it comes to coffee, we tend to rush things, throwing it down our throats to get that precious caffeine pumping through our veins as quickly as possible. Like with any kind of meditation, practice makes truly losing yourself to the experience easier. For example, the more practiced your taste buds are, the easier it is to:

• Identify flavor components

• Feel viscosity

• Be aware of lingering and changing characteristics

As you become more familiar with the way to thoroughly taste your coffee, you can find a greater depth of enjoyment in every sip of every great coffee you drink. You’ll find it easier to identify the less-than-stellar coffees, too, in addition to really getting in touch with the elements you love.

Training Yourself to Taste

There is a lot that goes into the tasting process. It’s not just about sitting and sipping in silence. It all starts with a better understanding of your sense of taste. Like all of our senses, taste has its roots in basic survival. Back in the times before artificial flavors, our sense of taste helped us pick out foods high in nutrition and identify others that might have spoiled or been poisonous.

Taste is the chemical recognition of molecules on our tongues. The tongue has five types of taste receptors that work together to create the full sensation of a taste. These receptors register sweetness, saltiness, bitterness, sourness, and savoriness (sometimes called ‘umami’ or meaty taste). Each has its own specific job to do when something hits our tongue. We register sugar content on the sweetness receptors, sodium chloride on the saltiness receptors, acids on the sourness receptors, and so on. With these five signals, the brain (somewhat mysteriously) builds us hugely complex and widely varying taste profiles for everything that touches a taste bud, intentionally or otherwise.

Of course, taste is not solely the product of our tongues but includes all of the amazing things our olfactory systems can bring to the sensory table, as well as the textures and temperatures felt by our senses of touch. Eating and drinking engage all five of our senses, but the taste, smell, and touch trifecta really does the heavy lifting.

When I say ‘tasting process’, it’s this trifecta that I’m referring to, and when it comes to coffee, it’s broken down into aroma, taste, and mouthfeel. For your mindful tasting experience, be present with each of these aspects individually and with all of them together. In other words, shift your focus to the small details of the experience, then let those enhance your awareness of the whole, and then shift back.

Aroma

There are two ways to perceive coffee aroma. You can sense it nasally, smelling the coffee through the nose, or retronasally, backwards to the nasal passage from the mouth or after swallowing. The aroma is said to be the most important attribute of specialty coffee. Today, more than 800 aromatic compounds have been identified in coffee, with more discovered every year. While all coffee has at least a small amount of a reasonable number of these compounds, there are many factors, from growing and roasting to grinding and brewing, that affect their concentration and expression.

Each compound adds to the complexity of the aroma, making it smell fruity or honey-like, roasty, earthy, buttery, spicy, floral, nutty, and even caramel-, chocolate- or vanilla-like. Of course not all of these compounds produce the best smells, and minimizing those while accentuating others is part of the art (and science) of making great coffee.

Take the time to experience the aroma of your coffee from every angle. Breathe it in on those first curls of steam as it brews. Sniff it before your first sip, then inhale and let it waft up retronasally. Be present with aroma. How does it change for you after it hits your tongue? What flavors come out as the coffee cools? Take it all in.

Taste

We’ve already talked a bit about taste generally. When it comes to coffee, things are a little different. The savoriness or umami element of taste plays little role in coffee tasting because coffee lacks the glutamate these receptors require. In spite of this only leaving four types of taste receptors, we still discuss five elements present in the taste of coffee: acidity, bitterness, sourness, saltiness, and sweetness.

While acidity should technically fall under sourness because of the receptors being triggered to produce the sensation, it’s broken out because it’s considered a favorable attribute, as opposed to sourness. If you taste a strong, unpleasant vinegar or acetic acid flavor, that’s sourness. If the coffee has a pleasant sharpness to it, that’s acidity.

Use every part of your tongue to taste the coffee. Swish it. Let it coat your mouth, then rinse with water and experiment with individual parts of your tongue. How does it taste up front? In the back? On the sides? The myth of specific regions of the tongue being solely responsible for certain tastes has been debunked, but you do have concentrations of different receptors in different areas, so play around with the different tastes, and remember to breathe to engage your olfactory system.

Mouthfeel

If you’ve been swishing coffee around in your mouth, you’ve undoubtedly noticed the mouthfeel. There are two main components to mouthfeel in coffee, and neither involves whether you burnt yourself because you didn’t wait for it to cool. Mouthfeel is all about body and astringency.

When you consider the body of a coffee, think about how full it feels. You want robust, whole-mouth sensations, not thin, watery, quick-to-fade flavors. Astringency is an undesirable attribute that leaves your mouth feeling dry. It can be nice to switch between coffee and a nice cool glass of water, but it shouldn’t be necessary to do it for fear of having your tongue shrivel up. Coffees with low astringency can feel refreshingly crisp or decadently creamy.

As you explore the aroma and taste of your coffee, pay attention to how it feels in your mouth. How does the mouthfeel affect the flavor? How do different roasts feel? Different brewing methods?

As you take yourself through aroma, taste, and mouthfeel, pay attention to how they change over time. A coffee’s finish is just as important as its first impression. How does the coffee change as you drink it? Does retain its character or fall apart as it cools?

All of these things will help you elevate your tasting experience, and over time, you’ll find it’s easier to be fully present with your coffee. Every step of the process, from opening the bag of beans to letting that last drop hit your tongue, is worth the attention. Mindfulness can change your entire outlook on life. Why not start with a cup of good coffee?

A BIG thank you to Karl Fendelander of Biggest Little Group for compiling my thoughts into this wonderfully written and expressive Post.